British culture and history are a rich tapestry woven from the traditions, ancient migrations, and innovations of the peoples who have inhabited the islands of the United Kingdom—England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland—over millennia. Long before the arrival of the Celts, who would later shape much of Britain’s Iron Age identity, the land was home to a diverse array of early inhabitants, from Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers to Neolithic farmers and the enigmatic Beaker people. This article delves into the pre-Celtic foundations of Britain, tracing the archaeological and historical threads that contribute to the nation’s cultural heritage.

The story of human life in Britain begins in the Palaeolithic period, or “Old Stone Age,” a vast epoch stretching from the earliest use of stone tools around 3.3 million years ago to approximately 11,650 years ago. Evidence of human presence in Britain dates back to at least 500,000 years ago, with finds linked to Homo heidelbergensis, an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans. Later, between 300,000 and 35,000 years ago, Neanderthals roamed the region, leaving behind tools and traces of their existence.

By around 9,000 BC, during the Mesolithic period (a transitional phase following the Palaeolithic), hunter-gatherers had established a foothold in Britain. These early inhabitants likely crossed a land bridge from mainland Europe during the last Ice Age, when sea levels were lower. Archaeological discoveries, such as flint tools and animal bones, reveal a nomadic lifestyle centred on hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants. Around 8,000 BC, as the climate warmed and temperatures rose higher than today, birch woodlands spread rapidly across the landscape, providing resources and shelter for these resilient communities.

The Mesolithic people, who occupied Britain by 9,000 BC, faced significant environmental shifts. A notable cold spell around 6,200 BC, lasting approximately 150 years, tested their adaptability. Known as the “8.2 kiloyear event,” this abrupt cooling was caused by the sudden drainage of glacial lakes in North America, disrupting ocean currents. Despite this challenge, the Mesolithic inhabitants persisted, relying on their deep knowledge of the land and its resources. Their legacy is preserved in sites like Star Carr in North Yorkshire, where archaeologists have uncovered evidence of sophisticated wooden platforms and deer antler headdresses, hinting at complex cultural practices.

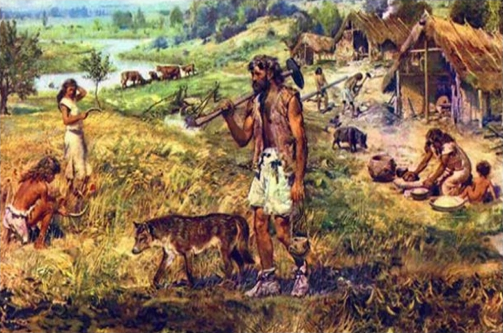

Around 4,000 BC, a profound shift occurred as Neolithic farmers arrived in Britain, marking the transition from a hunter-gatherer existence to settled agricultural life. Genetic studies, such as those published by the Natural History Museum, reveal that these newcomers carried significant ancestry from the earliest farming communities of Anatolia (modern-day Türkiye). This migration, accompanied by the introduction of farming techniques, reshaped Britain’s landscape and society. They cultivated crops like wheat and barley, domesticated animals such as cattle and sheep, and constructed monumental structures like Stonehenge, which remains an enduring symbol of their ingenuity.

The arrival of Neolithic farmers represents a cultural turning point, laying the groundwork for permanent settlements and communal traditions that would influence British identity for millennia.

Around 2,500 BC, the Beaker culture emerged in Britain, arriving from the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal). Named for their distinctive bell-shaped pottery, the Beaker people brought with them advanced metallurgy and new social practices. The Beaker people introduced bronze tools and weapons, ushering Britain into the Bronze Age. Their burial sites, often accompanied by finely crafted pots and metal artifacts, reflect a society with sophisticated trade networks and a reverence for the afterlife. Sites like the Amesbury Archer’s grave near Stonehenge provide a window into their world, revealing a blend of local and continental influences.

The pre-Celtic inhabitants of Britain—Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, Mesolithic survivors, Neolithic farmers, and Beaker innovators—laid the groundwork for the cultural mosaic that defines the United Kingdom today. Their contributions are not merely archaeological footnotes but enduring threads in the fabric of British identity. The resilience of the hunter-gatherers, the agricultural revolution of the Neolithic, and the technological leaps of the Beaker people collectively shaped a land that would later absorb Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman influences.

British culture, as we understand it now, is a fusion of the histories and traditions of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Yet its deepest roots lie in these ancient peoples, whose lives were shaped by the rhythms of the land and the challenges of survival. From the stone tools of the Palaeolithic to the monumental stones of the Neolithic and the bronze craftsmanship of the Beaker era, their legacies endure as a testament to human adaptability and creativity. This journey through pre-Celtic Britain reveals a land of constant change, where each wave of inhabitants left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape that would one day become the United Kingdom.

British culture and history, as we know it today, reflect the combined heritage of England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Following the pre-Celtic inhabitants—Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, Neolithic farmers, and Beaker people—the Celts dominated Britain by the Iron Age, their tribal societies thriving until the arrival of the Romans. Here we continue the story of Modern Britain; its evolution through subsequent waves of invaders and settlers up to the present.

In 43 AD, under Emperor Claudius, Roman legions invaded Britain, establishing the province of Britannia. The Romans subdued much of the Celtic population south of what is now Scotland, building roads, towns like Londinium (London), and fortifications such as Hadrian’s Wall to keep out the unconquered Picts and Caledonians in the north. A Romano-British culture emerged, blending Celtic traditions with Roman governance, Latin language, and infrastructure. By 410 AD, as the Western Roman Empire weakened under barbarian pressures, Emperor Honorius recalled the legions, leaving Britain to fend for itself.

After the Roman withdrawal, Britain fragmented into small kingdoms vulnerable to invasion. From the 5th century, Germanic tribes—Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—crossed the North Sea from modern-day Germany and Denmark. Initially arriving as mercenaries to aid Romano-British leaders against Pictish and Irish raids, they soon settled, establishing kingdoms like Wessex, Mercia, and Northumbria. By the 7th century, these Anglo-Saxon settlers had displaced much of the Celtic population in the east and south, pushing them into Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. Their Old English language and pagan beliefs gradually gave way to Christianity, spurred by missionaries like St. Augustine in 597 AD. This period, often called the “Dark Ages” due to scarce written records, saw the seeds of English identity take root.

While Anglo-Saxons dominated the south, northern Britain remained a Celtic stronghold. The Picts, a mysterious people in what is now eastern Scotland, resisted Roman and later Anglo-Saxon incursions. Known for their carved symbol stones, they spoke a Brittonic language akin to Welsh. To their west, the Scots—Gaelic speakers from Ireland—established the kingdom of Dál Riata in Argyll. By the 9th century, under King Kenneth MacAlpin, the Picts and Scots united to form Alba, the precursor to Scotland, blending their Celtic traditions into a distinct northern identity.

In 793 AD, Viking raiders from Scandinavia struck the monastery at Lindisfarne, marking the start of a turbulent era. These Norse warriors, skilled seafarers, pillaged Britain’s coasts before settling in the 9th century. The Great Heathen Army of 865 AD conquered much of eastern England, establishing the Danelaw—a region under Viking law stretching from Northumbria to East Anglia. Alfred the Great of Wessex resisted their advance, unifying Anglo-Saxon resistance and laying the groundwork for a united England. By 954 AD, Wessex had reclaimed the Danelaw, but Viking influence lingered in place names (e.g., York from Jorvik) and the English language, contributing words like “sky” and “knife.”

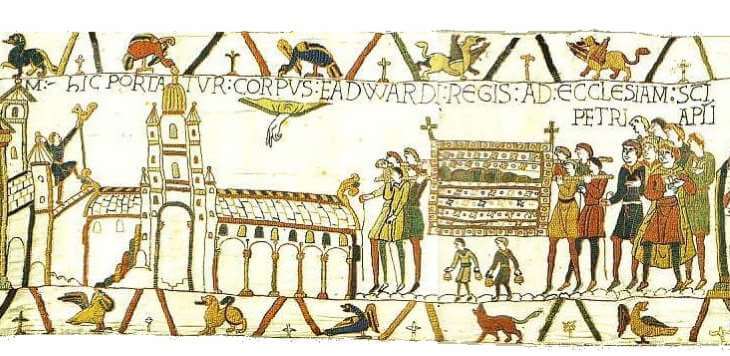

The year 1066 brought the last successful invasion of Britain. William the Conqueror, a Norman from northern France with Viking ancestry, defeated King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. The Normans imposed feudalism, built castles, and introduced French as the language of the elite. Though they ruled rather than replaced the Anglo-Saxon population, their influence reshaped governance, law (e.g., the Domesday Book), and architecture. Middle English emerged as a blend of Old English and Norman French, cementing a linguistic legacy still evident today.

Post-Norman Britain saw the consolidation of England, Wales, and Scotland as distinct entities. England annexed Wales in 1282 under Edward I, while Scotland resisted English domination, notably at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. The Picts faded into Scottish history, absorbed by Gaelic and Anglo-Norman influences. The medieval period brought cultural flourishing—Gothic cathedrals, Chaucer’s writings—and turmoil, including the Black Death and the Wars of the Roses, ending with the Tudor victory in 1485.

The Tudor and Stuart eras transformed Britain. Henry VIII’s break with Rome in 1534 established the Church of England, while Elizabeth I’s reign saw the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) and the beginnings of overseas exploration. The 1603 Union of the Crowns united England and Scotland under James VI and I, though full political union came later. The English Civil War (1642-1651) and the Glorious Revolution (1688) solidified parliamentary power, setting Britain on a path to constitutional monarchy and global empire.

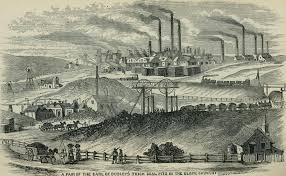

The 1707 Acts of Union formally united England and Scotland into Great Britain, later joined by Ireland in 1801. The Industrial Revolution, beginning in the 18th century, turned Britain into the “workshop of the world,” fuelled by innovations like the steam engine and textile machinery. The British Empire expanded across Asia, Africa, and the Americas, spreading English culture and language globally. Yet, this era also saw social upheaval, from the slave trade’s abolition in 1833 to labour reforms.

The 20th century tested Britain with two world wars. Victory came at a cost: the empire dissolved post-1945, with India’s independence in 1947 marking a turning point. The 1921 partition of Ireland created Northern Ireland, part of the UK, while the Republic of Ireland emerged separately. Post-war immigration from the Commonwealth changed Britain’s demographics to a more multicultural fabric, evident in cities like London today. The European Union era (1973-2020) and Brexit reflect ongoing debates about identity and sovereignty. Modern British culture—rooted in its Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman past—continues to evolve, blending tradition with global influences.

Resilience and Adaptability

Community and Cooperation

Fairness and Justice

Individual Liberty

Pragmatism and Innovation

Respect for Tradition

Love of the Land

These values—resilience, community, fairness, liberty, tolerance, pragmatism, tradition, and love of the land—emerge from Britain’s layered history. They were forged by the survival strategies of early inhabitants, refined by Roman and medieval systems, tested by invasions and upheavals, and adapted through imperial and industrial eras into the modern age. Today, the UK government identifies related principles like democracy, rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect as “fundamental British values” in its educational and citizenship frameworks, in theory echoing these historical constants. Though it has become apparent, it is up to those who love these lands to ensure our cultural history and principles are upheld.

While not every value was universally upheld at all times—history includes episodes of injustice—their persistence across centuries underscores their role as cultural anchors. They connect the flint tools of the Palaeolithic to the streets of 21st-century Britain, illustrating a remarkable continuity amid change.

© The Uncensored Patriots - 2025. All rights reserved. Web design and maintenance by Consiliuma. Articles by TUP Community Members.